How PyXtal Works

PyXtal is a free, open source Python package intended to aid with crystal structure prediction and other purposes of crystal symmetry analysis. It is our aim to make our tools and theory freely available, in order to expand the knowledge and utilization of crystallographic symmetry. To this end, we outline the basic algorithms used by PyXtal. For more general information about crystallography, see the Background and Theory page.

Overview

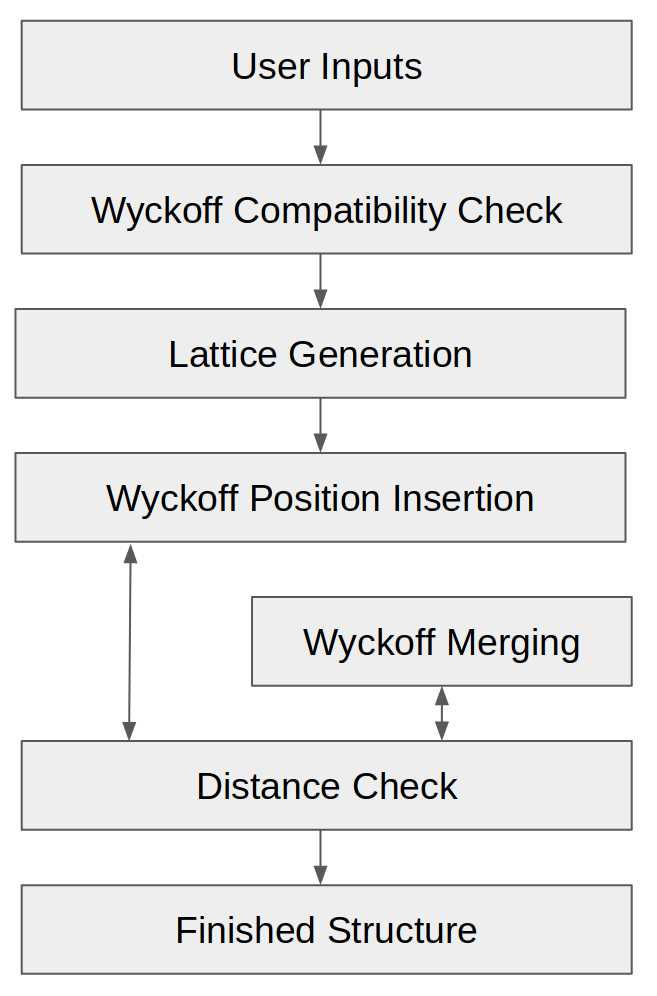

In order to generate random symmetrical crystals, PyXtal uses space groups and their Wyckoff positions as templates, then inserts atoms (or molecules) one Wyckoff position at a time, until the desired stoichiometry is reached. This ensures that the correct symmetry will be obtained, without the need to adjust atomic positions. Along the way, it checks that the atoms are sufficiently far apart. To generate a single random crystal, PyXtal performs roughly seven steps:

PyXtal Structure Generation Flowchart.

Get the input parameters from the user.

Check the compatibility of the stoichiometry with the space group.

Generate a random lattice consistent with the space group.

Begin placing atoms into Wyckoff positions, one atomic specie at a time.

Check that the atoms in the single Wyckoff position are not too close together. If the minimum distance is smaller than some tolerance (based on the atomic species), then we merge the Wyckoff position into a smaller special position.

Check the inter-atomic distance between the newly generated Wyckoff position and the previously generated positions. If the distances are too close, we choose a new generating point within the same original Wyckoff position. For molecular crystals, we also attempt to reorient the molecule, so as to reduce the distance between atoms.

Continue to place Wyckoff positions and species into the crystal, until the proper stoichiometry is reached. If any step between 3-6 fails, we repeat it, up to a pre-determined maximum number of attempts.

If the generation succeeds, the resulting crystal can be (energetically) optimized and compared with other possible structures. After many attempts, the lowest-energy structure will be the one most likely to exist at the specified conditions. This can be used, for example, to determine the phase diagram of a solid without the need to perform any experiments.

Next, we explain the steps listed above in greater detail.

User Input

This includes the crystal’s stoichiometry, space group, and volume factor. Optionally, the desired lattice and allowed inter-atomic distances can also be defined (which is useful for testing at higher pressures). Otherwise, these parameters will be chosen automatically.

Checking Compatibility

Before attempting to generate a structure, PyXtal must make sure it is possible to do so. The WP’s in different space groups have different multiplicities. As a result, not every number of atoms is compatible with every space group. For example, consider the space group Pn-3n (222).

$ pyxtal_symmetry -s 222

-- Space group # 222 (Pn-3n)--

48i site symm: 1

...

...

...

6b site symm: 42 . 2

3/4, 1/4, 1/4

1/4, 3/4, 1/4

1/4, 1/4, 3/4

1/4, 3/4, 3/4

3/4, 1/4, 3/4

3/4, 3/4, 1/4

2a site symm: 4 3 2

1/4, 1/4, 1/4

3/4, 3/4, 3/4

The smallest Wyckoff position is 2a, with the next smallest being 6b. It is impossible to create a crystal with 4 atoms in the unit cell for this symmetry group, because no combination of Wyckoff positions adds up to 4. The position 2a cannot be repeated, because it falls on the exact coordinates (1/4, 1/4, 1/4) and (3/4, 3/4, 3/4). A second set of atoms in the 2a position would overlap the atoms in the first position, but this is not physically possible.

Thus, it is necessary to check the input stoichiometry against the Wyckoff positions of the desired space group. To accomplish this, PyXtal iterates through all possible Wyckoff position combinations within the confines of the stoichiometry. As soon as one valid combination is found, the check returns True. If no valid combination is found, the check returns False, and the generation attempt fails with a warning.

Some space groups allow valid combinations of WP’s, but may not give many degrees of freedom for generation. It may also be the case that the allowed combinations result in atoms which are too close together. In these cases, PyXtal will attempt generation as usual: until the maximum limit is reached, or until a successful generation occurs. If generation repeatedly fails for a given combination of space group and stoichiometry, the user should make note and avoid the combination going forward.

Lattice Generation

The first step in PyXtal’s structure generation is the choice of unit cell. Depending on the symmetry group, a specific type of lattice must be generated. For all crystals, the conventional cell choice is used to avoid ambiguity. The most general case is the triclinic cell, from which other cell types can be obtained by applying various constraints.

To generate a triclinic cell, 3 real numbers are randomly chosen (using a Gaussian distribution centered at 0) as the off-diagonal values for a 3x3 shear matrix. Treating this matrix as a cell matrix, one obtains 3 lattice angles. For the lattice vector lengths, a random 3-vector between (0, 0, 0) and (1, 1, 1) is chosen (using a Gaussian distribution centered at (0.5, 0.5, 0.5)). The relative values of the x, y, and z coordinates are used for a, b, and c respectively, and scaled based on the required volume.

For other cell types, any free parameters are obtained using the same methods as for the triclinic case, along with any necessary constraints. In the tetragonal case, for example, all angles must be 90 degrees. Thus, only a random vector is needed to generate the lattice constants.

For molecular crystals, the issue of generating the lattice is also dependent on molecular orientation. Thus, the lattice must be checked for every molecule in the crystal. To do this, the atoms in the original molecule are checked against the atoms in periodically translated copies of the molecule. Here, standard atom-atom distance checking is used.

Generation of Wyckoff Positions

The central building block for crystals in PyXtal is the Wyckoff position (WP). Once a space group and lattice are chosen, WP’s are inserted one at a time to add structure.

PyXtal starts with the largest available WP, which is the general position of the space group. If the number of atoms required is equal to or greater than the size of the general position, the algorithm proceeds. If fewer atoms are needed, the next largest WP (or set of WP’s) is chosen, in order of descending multiplicity. This is done to ensure that larger positions are preferred over smaller ones; this reflects the greater prevalence of larger multiplicities both statistically and in nature.

Checking Inter-atomic Distances

To produce structures with realistic bonds and bond lengths, the generated atoms should not be too close together. In PyXtal this means that by default, two atoms should be no closer than the covalent bond length between them. However, for a given application the user may decide that shorter or longer cutoff distances are appropriate. For this reason, PyXtal has a custom tolerance matrix class which allows the user to define the distances allowed between any two types of atoms.

Because crystals have periodic symmetry, any point in a crystal actually corresponds to an infinite lattice of points. Likewise, any separation vector between two points actually corresponds to an infinite number of separation vectors. For the purposes of distance checking, only the shortest of these vectors are relevant. When a lattice is non-Euclidean, the problem of finding shortest distances with periodic boundary conditions is non-trivial, and the general solution can be computationally expensive cite{LatticeProblem}. So instead, an approximate solution is used based on assumptions about the lattice geometry:

For any two given points, PyXtal first considers only the separation vector which lies within the central unit cell spanning between (0, 0, 0) and (1, 1, 1). For example, if the original two (fractional) points are (-8.1, 5.2, -4.8) and (2.7, -7.4, 9.3), one can directly obtain the separation vector (-10.8, 12.6, -14.1). This is then translated to the vector (0.2, 0.6, 0.9), which lies within the central unit cell. PyXtal also considers those vectors lying within a 3x3x3 supercell centered on the first vector. These would include (1.2, 1.6, 1.9), (-0.8, -0.4, -0.1), (-0.8, 1.6, 0.9), etc. This gives a total of 27 separation vectors to consider. After converting to absolute coordinates, one can calculate the Euclidean length of each of these vectors and thus find the shortest distance.

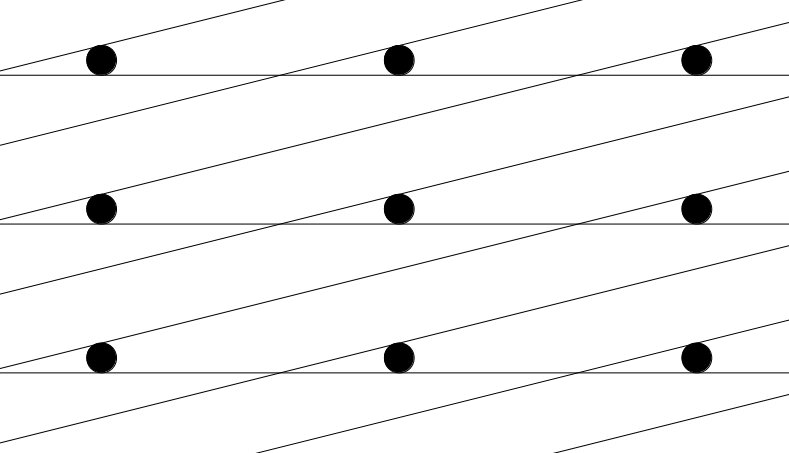

Note that this does not work for certain vectors within some highly distorted lattices. Often the shortest Euclidean distance is accompanied by the shortest fractional distance, but whether this is the case or not depends on how distorted the lattice is. However, because all lattices are required to have no angles smaller than 30 degrees or larger than 150 degrees, this is not an issue.

Distorted Unit Cell. Due to the cell’s high level of distortion, the closest neighbors for a single point lie more than two unit cells away. In this case, the closest point to the central point is located two cells to the left and one cell diagonal-up. To find this point using PyXtal’s distance checking method, a 5x5x5 unit cell would be needed. For this reason, a limit is placed on the distortion of randomly generated lattices.

For two given sets of atoms (for example, when cross-checking two WP’s in the same crystal), one can calculate the shortest inter-atomic distances by applying the above procedure for each unique pair of atoms. This only works if it has already been established that both sets on their own satisfy the needed distance requirements.

Thanks to symmetry, it is not necessary to calculate every atomic pair between two Wyckoff positions. For two Wyckoff positions A and B, one need only calculate either the separations between one atom in A and all atoms in B, or one atom in B and all atoms in A. This is because the symmetry operations which duplicate a point in a Wyckoff position also duplicate the separation vectors associated with that point. This is also true for a single Wyckoff position; for example, in a Wyckoff position with 16 points, only 16 calculations are needed, as opposed to 256. This can significantly speed up the calculation for larger Wyckoff positions.

For a single WP, it is necessary to calculate the distances for each unique atom-atom pair, but also for the lattice vectors for each atom by itself. Since the lattice is the same for all atoms in the crystal, this check only needs to be performed on a single atom of each specie. For atomic crystals, this just means ensuring that the generated lattice is sufficiently large.

For molecules, the process is slightly more complicated. Depending on the molecule’s orientation within the lattice, the inter-atomic distances can change. Additionally, one must calculate the distances not just between molecular centers, but between every unique atom-atom pair. This increases the number of needed calculations, in rough proportion to the square of size of the molecules. As a result, this is typically the largest time cost for generation of molecular crystals.

Merging and Checking Wyckoff Positions

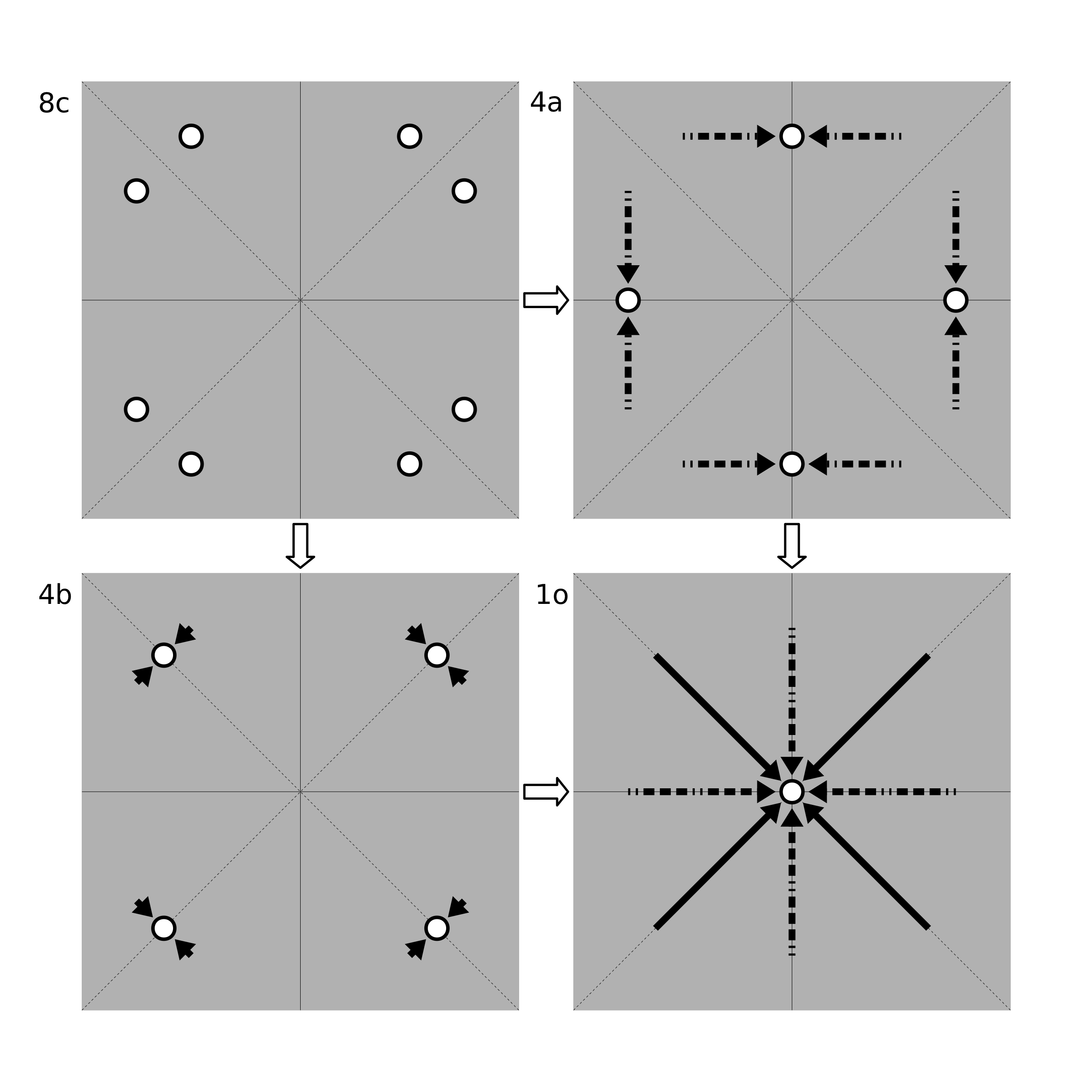

Once a WP is chosen, a random 3-vector between (0, 0, 0) and (1, 1, 1) is created. This acts as the generating point. Projecting this vector into the WP, one obtains a set of coordinates in real space. Then, the distances between these coordinates are checked. If the atom-atom distances are all greater than a pre-defined limit, the WP is kept and the algorithm continues. If any of the distances are too small, it is an indication that the WP would not occur with that generating point. In this case, the coordinates are merged together into a smaller WP, if possible. This merging continues until the atoms are no longer too close together (see below).

Wyckoff Position Merging Example. Shown are possible mergings of the general position 8c of the 2D point group 4mm. Moving from 8c to 4b (along the solid arrows) requires a smaller translation than for 4a (along the dashed arrows). Thus, if the atoms in 8c were too close together, PyXtal would merge them into 4b instead of 4a. The atoms could be further merged into position 1o by following the arrows shown in the bottom right image.

To merge into a smaller position, the original generating point is projected into each of the remaining WP’s. The WP with the smallest translation between the original point and the transformed point is chosen, so long as the new WP is a subset of the original one, and so long as the new points are not too close together. If the atoms are still too close together, the WP is discarded and another attempt is made.

Once a satisfactory WP has been filled, the inter-atomic distances between the current WP and the already-added WP’s are checked. If all distances are acceptable, the algorithm continues. More WP’s are then added as needed until the desired number of atoms has been reached. At this point, either a satisfactory structure has been generated, or the generation has failed. If the generation fails, then either smaller distances tolerances or a larger volume factor might increase the chances of success. However, altering these quantities too drastically may result in less realistic crystals. Common sense and system-specific intuition should be applied when adjusting these parameters.

Finding Valid Molecular Orientations

In crystallography, atoms are typically assumed to be point particles with no well-defined orientation. Since the object occupying a crystallographic Wyckoff position is usually an atom, it is further assumed that the object’s symmetry group contains the Wyckoff position’s site symmetry as a subgroup. If this is the case, the only remaining condition for occupation of a Wyckoff position is the location within the unit cell. However, if the object is instead a molecule, then the Wyckoff position compatibility is also determined by orientation and shape.

To handle the general case, one must ensure that the object 1) is sufficiently symmetric, and 2) is oriented such that its symmetry operations are aligned with the Wyckoff site symmetry. The result is that different point group symmetries are compatible with only certain Wyckoff positions. For a given molecule and Wyckoff position, one can find all valid orientations as follows:

Determine the molecule’s point group and point group operations. This is currently handled by Pymatgen’s build-in PointGroupAnalyzer class, which produces a list of symmetry operations for the molecule.

Associate an axis to every symmetry operation. For now, it can be assumed that the axis is centered at the origin. For a rotation or improper rotation, use the rotational axis. For a mirror plane, use an axis perpendicular to the plane. Note that inversional symmetry does not add any constraints, since the inversion center is always located at the molecule’s center of mass.

Find up to two non-collinear axes in the site symmetry and calculate the angle between them. Find all conjugate operations (with the same order and type) in the molecular point symmetry with the same angle between the axes, and store the rotation which maps the pairs of axes onto each other. For example, if the site symmetry were

mmm, then choose two reflectional axes, say the x and y axes or the y and z axes. Then, look for two reflection operations in the molecular symmetry group. If the angle between these two operation axes is 90 degrees, store the rotation which maps the two molecular axes onto the Wyckoff axes for every pair of reflections with 90 degrees separating them.For a given pair of axes, there are two rotations which can map one onto the other, with opposite directions of the molecular axis. Depending on the molecular symmetry, these two rotations may produce the same molecular orientation. Using the list of rotations calculated in step 3, remove redundant orientations which are equivalent to each other.

For each found orientation, check that the rotated molecule is symmetric under the Wyckoff site symmetry. To do this, simply check the site symmetry operations one at a time by transforming the molecule and checking for equivalence with the untransformed molecule.

For the remaining valid rotations, store the rotation matrix and the number of degrees of freedom. If two axes were used to constrain the molecule, then there are no degrees of freedom. If one axis is used, then there is one rotational degree of freedom, and store the axis about which the molecule may rotate. If no axes are used (because there are only point operations in the site symmetry), there are three (stored internally as two) degrees of freedom, meaning the molecule can be rotated freely in 3 dimensions.

PyXtal performs these steps for every Wyckoff position in the symmetry group and stores the nested list of valid orientations. When a molecule must be inserted into a Wyckoff position, an allowed orientation is randomly chosen from the list. This forces the overall symmetry group to be preserved, because symmetry-breaking positions are not allowed.

It is worth noting that the general position of any symmetry group always has site symmetry group 1. This means that any molecule can always be inserted into the general position with any orientation. However, many real crystals have molecules located in special positions, and thus this method alone is insufficient for generating realistic structures [1].

Another important consideration is whether a symmetry group will produce inverted copies of the constituent molecules. In many cases, a chiral molecule’s mirror image will possess different chemical or biological properties cite{chirality}. For pharmaceutical applications in particular, one may not want to consider crystals containing mirror molecules. By default, PyXtal does not generate crystals with mirror copies of chiral molecules. The user can choose to allow inversion if desired.